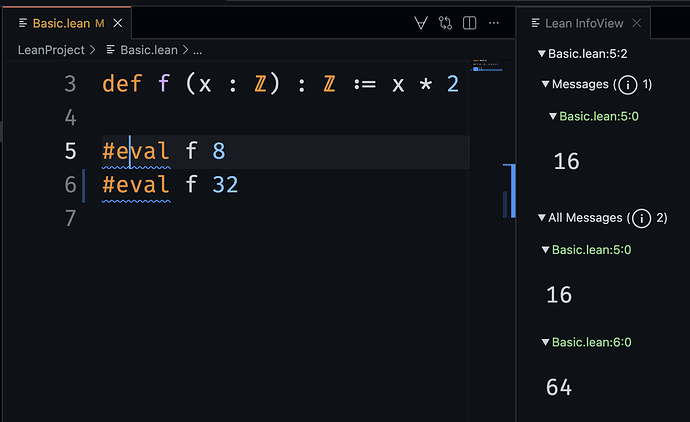

Lean4 has a feature that is awesome for teaching, learning, and incremental programming: real-time evaluation of source code expressions in the editor, without the need to compile or run code manually.

This is done by writing the command #eval underneath your definitions.

def f (x : ℤ) : ℤ := x * 2

#eval f 8 -- 16

#eval f 16 -- 32

This is similar to interactive notebooks for Python and worksheets.sc for Scala, but has the advantage that it can be used in real practical codebases with no setup burden, rather than being limited to purely educational and literature contexts.

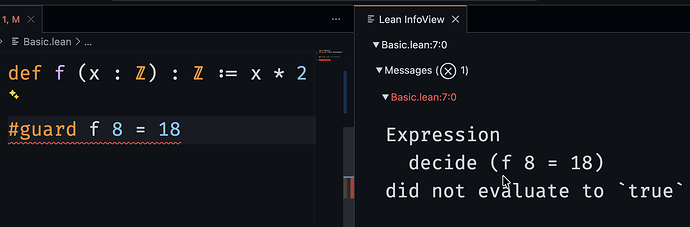

There is also a #guard command which serves as in-source unit tests that can be left in source to serve as documentation.

#guard f 8 = 18 -- error, not true

Which is a huge win for reducing the overhead of unit testing – I personally used to be a passionate advocate for writing tests, yet over the years have stopped entirely out of framework-fatigue. I find it too cumbersome in Scala to justify for smaller projects. (I hate the directory structure it imposes, I hate needing to memorize and use library constructs like assertEquals, needing to write verbose class declarations for test suites, needing to write english descriptions of tests as strings, needing to re-research how to set up the build tooling for it on every new project, etc..) not to mention how inaccessible it is for beginners.

Having a simple way to write simple in-source unit tests would make it feel much more worthwhile. Rust is another language that offers this.

I would love to see something like this in Scala. Given that we already have .worksheets.sc and websites like Scastie for evaluating top-level expressions, I assume the architecture is mostly there?

Pre-Proposal Idea: ‘#‘ as a new top-level keyword

As far as I know, the most sensible implementation for Scala would be to do exactly what .worksheet already does, but for all .scala files now and activated only on lines that begin with a special keyword (I propose # as I think this is a free symbol in the language), e.g.

def f(x: Int): Int = x * 2

# f(8) // 16

I don’t think we should offer multiple forms like Lean does in distinguishing #eval from #guard. Rather, I think we should only offer #, and just interpret boolean expressions as unit tests that emit IDE errors when they evaluate to false

def f(x: Int): Int = x * 2

# f(8) // 16 (for temporary experimentation, you'll delete this)

# f(6) == 12 // ✅ true (a unit test, you'll commit this)

# f(6) == 22 // ❌ false (a unit test failing, emits a file error until fixed)

Simpler and more elegant.

Feedback and ideas appreciated. How feasible would this be to implement in the compiler and vscode? What would I start with if I wanted to experiment on getting this to work on my own?