Writing code has never been the problem here. Choosing what to support for 10+ years as part of the standard library is a different call from dropping some code on Github.

I tend to agree.

Now, I wouldn’t normally think this warrants adding a new type… except that this would be a fantastic opportunity to introduce a no-overhead/unboxed Result type to Scala!

That is, a type that does not allocate a wrapper on success (most of the time).

Indeed, I think we can represent successful values of Result[T,E] as T itself and failures as Failure[E] — that is, unless the successful T value is an instance of Failure (e.g. if the user calls Success(Failure(e))), in which case we have to wrap it into a Success class, to distinguish it from proper failures.

In general, there will need to be as many Success wrappers as there are nested successes which end on a Failure. All other nested successes should avoid wrapping.

object Success {

def apply[A](a: A): Result[A, Nothing] = (a match {

case _: Failure[_] | _: Success[_] => new Success(a)

case _ => a

}).asInstanceOf[Result[A, Nothing]]

}

This is similar to @sjrd’s unboxed option approach.

See also the relevant discussion here.

As far as renaming, I’m opposed. Names should reflect what something is, not how you expect it to be used. That goes for parameter names and it goes for class names and everything else.

For anyone that wants a rename, or is for some reason jealous of the Rust learning curve, I think the real issue here is documentation. The Scala documentation situation is really poor. It used to be a lot worse, but it’s not good enough.

There are any number of things like this I can point to. People used to say Scala is too complex, especially all its advanced types, but you don’t hear that since Typescript came out. For some reason people have no issue with writing really crazy types. And the number of pitfalls I see people hitting in C# is staggering, but I never hear those people criticizing C#.

IMO what we have is a messaging problem. There’s no one place that someone can go to and read the answers to everything they need to know. People are fine with Typescript’s insane types because they have an official doc book that covers everything in very easy-to-understand English. And because it solves an important need and that’s what everyone’s using. Same with C#. They aren’t always comparing themselves to everyone else. I think Scala has got an inferiority complex.

So again, the reason why people learning Rust find what Result does more intuitive that how people learning Scala find Either, is because of how it’s taught, or not – plain and simple.

As far as error accumulation, we could add some helpers to the library for Either[List[E], A].

We debated this here:

I felt it made sense to right bias Either given the decision was made that partial unification in Scala would work like it does in Haskell, always going from left to right (right biased). It makes more since in Haskell because value-level and type-level functions always take a single argument (if I understand correctly). In Scala you can have multi-argument functions, thus it is much more arbitrary to pick left to right, and it is an inconsistency between value and type levels in Scala.

The alternative that I proposed in that debate, which I think was a better fit for Scala (up side), but was indeed more complex (down side), was that type functions should not partially apply by default. Only if there was some kind of annotation would they partially apply, and that annotation would say the direction: either left-to-right or right-to-left. Miles implemented something similar in his branch during that discussion but Adriaan ultimately vetoed it, and the Dotty team followed suit. I believe Miles’s implementation was right biased by default, left biased with an annotation. I agreed it was ugly and more complex. But what we settled on means that even something like a Result type that has Ok and Err as subtypes should almost certainly be right biased like Result[ErrType, OkType], not left biased like Result[OkType, ErrType].

At the time I felt that Either with a bit of cleanup could have been a nice type for balanced choices, where one of them did not represent a “success” and the other a “failure.” For example, a method might can take Either[File, String] for a filename. Either option is fine. One is not better than the other. Then a new type (like the Result proposed here) could be added where one side represented a desired value and the other an error. After Either was right biased, I implemented but have never released a Scalactic type that is a balanced either, kind of like the old Either, where you can select a “projection” monad on either side. The main problem I had was I couldn’t decide what to call the types, because I felt Either, Left, and Right were the best names for a balanced choice type.

Given partial unification works as it does, and Either is already right biased, I wonder if we could just deprecate the names Either, Left, and Right and change them over a good long time to Result, Err, and Ok. That might be better. Then after that long deprecation period has expired, we could remove Either, Left, and Right for a while, then bring it back as the balanced choice type we lost when we right biased Either, and call that Either, Left, and Right.

For reference here is documentation for Scalactic Or:

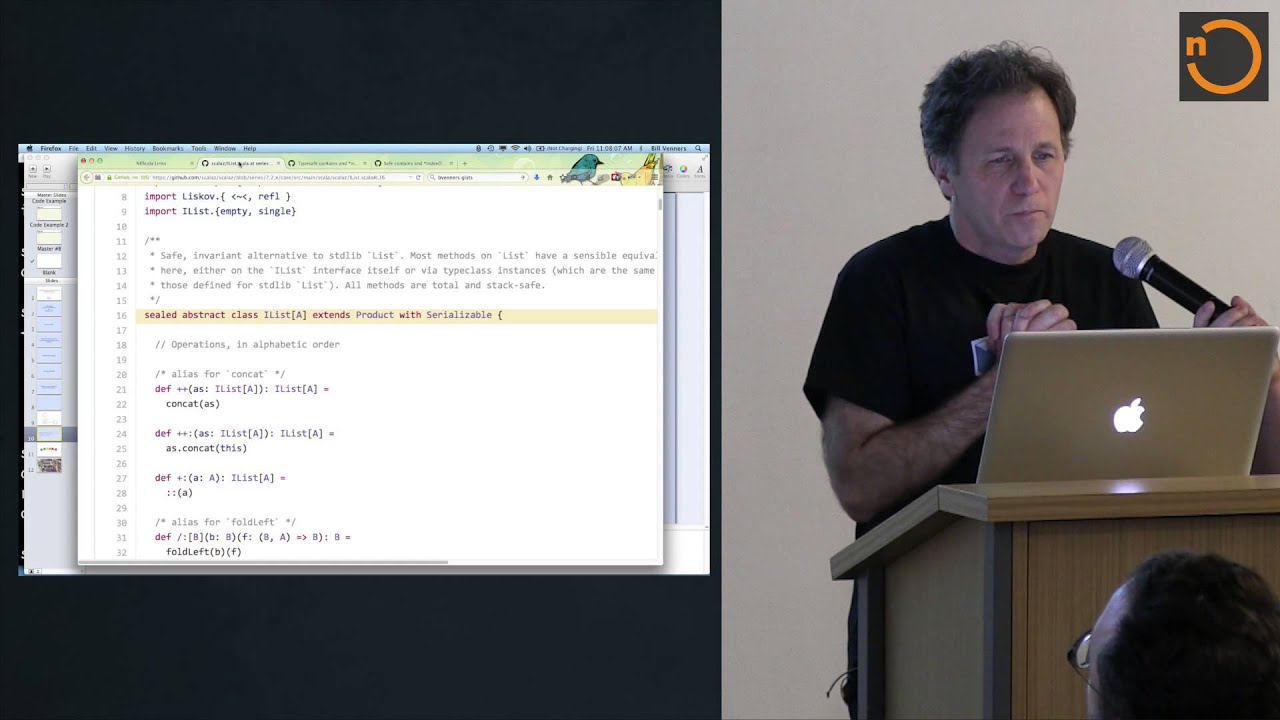

Here’s a talk I gave back in 2015 comparing Or with Scalaz’s disjunction and Validation types:

@bvenners Thanks for the historical perspective! I had overlooked the connection with partial unification. Renaming to Result, OK and Err while keeping right-bias is a possibility. But I also like @LPTK’s suggestion to eliminate boxing, which would probably require a new type.

Another possibility that was not brought up yet would be to make the error type a type member. I.e.

trait Result[+T] { type Err }

That would get around the partial unification issue, but risks being clunky, so I am not sure about it eiher.

IMO If a new data type will be introduced, it should be introduced outside the standard library, and should fight for its own mindshare separate from Either. Library and framework authors could easily adopt it, and over time if it becomes the de-facto standard it could be considered for inclusion in the standard library.

This way, when the final decision point comes, we can discuss a small number of known quantities, rather than a thousand different ideas limited only by people’s imagination.

This is not an unusual process. scala.concurrent.Future was basically incubated in akka/twitter-util, and there have been discussions for upstreaming com.lihaoyi:sourcecode due to its fundamental nature and widespread use.

If we didn’t get Either “right” after a tremendous amount of consultation and consensus, I don’t have any confidence a “fixed” result type would do any better, unless we have this incubation process to let it bake see if it truly meets the needs of the community. Any technical details of what kind of result type would be better are secondary to making sure we get the process right.

Either.cond is exactly how I would do it. Considering you would typically use it

Either.cond(weCanUseDesiredVAlue, desiredValue, fallbackValue)

it is just a convenience for

if(weCanUseDesiredValue) Right(desiredValue) else Left(fallbackValue)

I get it, you want the “Left” value to the left and the “Right” value to the right. But is it really important? No one will get this wrong by accident, because it won’t type check. And the “Right” value isn’t really on the left, it’s in the middle.

If the students ask, just say “historical reasons”. If they make rude jokes about it, laugh with them.

It sounds very scary if advancing a major version is seen as a compelling reason to remove not only very wart, but also every wrinkle and unwanted hair. It’s tempting to try to make everything perfect, but only time will tell what is best. Migration is going to be hell anyway, please make it not unnecessarily difficult.

Keep Either as it is and add an alternative. With trivial conversion between Either and alternative. If people really prefer the alternative, they will switch over gradually.

It would not be the exact same semantics because Either/Left/Right does not have any semantics to it.

I really hope that this is not a valid reason to swipe an idea from the table.

It would not be the exact same semantics because

Either/Left/Rightdoes not have any semantics to it.

It does, that’s why map maps on the right side and not on the left.

I really hope that this is not a valid reason to swipe an idea from the table.

You got me there. It was just my emotional response to an idea I don’t really agree with. Sorry.

Using Either for error handling is one of the worst cases of Haskellisms that got carried into Scala. Honestly Either should represent unions and if you want to represent errors you should be using Try instead. This also makes the intention in code much clearer (believe it or not I have spent a surprisingly large amount of time having to explain this to new people).

Right biased map should be present on Try, but for Either we should have leftMap and rightMap (or the equivalent).

But we are here now and we just copied something from another language without evaluating whether it made general sense or not and for historical (or other) reasons we just transformed Either into something is meant to be Try

My suggestion would be to add methods to scala.util.Try so that it has the same capabilities as current Either, and just treat Either as the union type which it actually originally was meant to be. We can then also add things like Applicative to Try (so that we can accumulate errors) which actually makes sense in the context of Try

What? Try is a very inflexible error-handling mechanism: your errors must be Throwables, you can’t restrict what kind of Throwable are errors, and you can’t even guarantee that you only get the errors you expect, because all of the combinators catch! I’m not saying that Try is bad, but it’s nothing close to a replacement for Either as it’s used in FP.

What’s the benefit? All you’re doing is increasing the amount of typing and making it not work with for-comprehensions.

This assumes that we have Applicative in stdlib, which I’m not opposed to, but if it’s a monad it can’t be an “accumulating” applicative. More fundamentally, how do you combine Throwables?

If something is an error it should be reflected in its type, thats why we use strongly typed languages. It should be standard practice that if you have some type that is an error that it should be indicated as such (often by implementing some sealed trait ADT that represents an error). Otherwise its not an error and then you should be using Either. Of course there is nothing wrong with having helper functions to convert an Either to a Try if you have something that wasn’t an error at one point that is now an error.

Also I am not talking about throwing exceptions here, I am talking about treating errors of values and such errors should be marked as such.

And yes Try is inflexible because all of the usability improvements happened to Either in Scala 2.12, remember left and right projections on Either?

We use Either for actual unions, and in this case the standard .map case is incredibly confusing.

The fact that Try’s left type is a Throwable is a diversion here. The left value of Try could be some other type, even just a market Trait that indicates its holding an error.

The main point I am making is distinguishing between representing a union and representing an error from a computation, because those two are very different things.

Even the documentation of Try which was written ages ago was meant to indicate this, i.e.

/**

* The `Try` type represents a computation that may either result in an exception, or return a

* successfully computed value. It's similar to, but semantically different from the [[scala.util.Either]] type.

*

* Instances of `Try[T]`, are either an instance of [[scala.util.Success]][T] or [[scala.util.Failure]][T].

*

* For example, `Try` can be used to perform division on a user-defined input, without the need to do explicit

* exception-handling in all of the places that an exception might occur.

Try was meant to be either our monad or applicative for dealing with errors. Its definitely an annoyance that its been coupled to Throwable, but that is something that could be rectified (Scala could implement its own error type which could be a Throwable or just a standard error which would be on the left of Try). Either that or people just had a really big aversion to entending Throwable.

I strongly agree with this post from @odersky . I would also be happy with introducing a Result type which is similar to the current Either but better indicates that its only meant to be for errors.

I have nothing against (or for) a Result class. I’d argue that a library like cats or any development team can, could, and should develop their own structures if the current ones don’t fit. Try/Success/Fail are a reasonable answer to Either. On the other hand, adding one or a few simple classes isn’t a huge deal.

A few things about Fail. If one is going to create an disciplined error framework, why not base it on one that exists? Throwable meets every need I’ve ever seen.

It does allow accumulating errors. All Throwable have an optional “cause.” They were intended to handle cascading errors from the first release of Java. Each throwable can fill its stack-trace. They can handle errors created by multiple and separate threads.

Throwable are designed to be specialized. IOException is the root of every (non-runtime) exception caused by I/O. Any and all libraries can create their own error definition structure. Because Throwable already supports cascading errors, a private library can always handle errors from other libraries.

With traits, one can add any kind of type graph one needs. Both Java and scala can match on any subclass of Throwable or trait/interface. It’s not a good idea to have a complicated error infrastructure. The current Throwable hierarchy allows anything that is needed. Including type parameters. If the error is caused by a single object, or a complex collection of objects, a library author can always add instance variables to the Throwable. Any type declaration can be used.

Throwables need not be thrown. That’s the whole purpose behind Try. It catches things that are throw outside to control of the current library and returns it without unwinding its context. It allows halting the computational chain, poisoning it, or even recovering it.

For implementation convenience, it would be nice if Option, Success, Fail, Nothing were all rolled up into one thing. From a modeling perspective, not so much so. I suspect the current problem is from version skew. If there was a AnyRef like trait that indicated the null set, they could all fall into the same type hierarchy. But they were all defined at different times, for different reasons, and its too late now. Without putting them all on the deprecated list at least.

If any library wants to do that, it certainly can. A NothingHere[T] trait, a SomethingHere[T] trait, an InvalidComputation[E<:Throwable] trait. The first two should be IterableOnce[T] to handle the same semantics as Option and Success. The later two would be used for pattern matching. It would even be possible to have a NothingHere[T] and InvalidComputation mix-in. I’m not sure that last one would be a good idea. Some mix of toOption, toSuccess, toFail may be in order for interface boundaries.

I’m indifferent to the change. Which probably means I don’t think it’s worth the time. If a unified framework for these concepts are created, Option, Try, Success, Fail should be deprecated. Probably never removed from the language, but to encourage people to use the new unified framework.

To be clear, I think the problem most folks have with Try is that its failure type is fixed at all, not that it’s fixed to Throwable.

This is my whole point though, if have you have errors they should be reflected in their type.

The problem with a fixed failure type is that it forces you to unsafely downcast if you want to access anything other than the members that are defined on that fixed type. This is either unsafe or underpowered, depending on how strongly you try to avoid unsafe casts.

Reflecting errors in the type doesn’t require paying the annoyance tax of restricting yourself to error types which extend Exception1, and Either can be used to convey this with far less fuss than Try:

type E // stand-in for whatever you use for errors

type Errors = NonEmptyList[E]

def foo[A]: Either[Errors, A]

- Specifically:

Exceptionsubclasses are annoying to compose, tempt junior devs to use them for flow control (see:Integer.parseValue), often provide no more information than aString, and are a right pain in the neck to test because they don’t provide sensible equality.

What does it mean to reflect an error int the type? Do you want a standard type to cover all errors, or do you want every one to use any type as long as it has “Error” in the name, or what are you asking for?

Okay to make things more clear, let me state this in a different way. If you are representing errors with basic types as String, i.e. Either[String, T] for some value T this is considered code smell. I have just gone through all of our backend applications at work and we never do this, and there are multiple reasons why.

- You can’t match on the string to catch a specific error (well technically you can but you would have to match on the contents of the string at which point you should just represent the error as a seperate type)

- Due to needing to compose errors of different types from different clients you invariable end up using some error

ADTtype, i.e. if you have something like this

Andfor { user <- getUser(someUser) tweet <- getTweetFromUser(tweet) } yield tweetgetUserreturns values of typeEither[UserNotFoundError, Unit]andgetTweetFromUserreturns values of typesEither[TweetNotFound, Unit]then you need some sane way to compose these values, and the only real practical way to do this is to have some type that marks that bothUserNotFoundErrorandTweetNotFoundare errors. The point is thatThrowablecan be this market type to indicate an error (there is an argument that something else should be used, this is explained later). Note that you can still usedsealed traitorsealed abstract classto make sure at compile time that a certain set of errors has exhaustivity checking, i.e.

This way when you match againstsealed abstract class UserErrors(errorMessage: String) extends GeneralError object UserErrors { case object UserNotFoundError extends UserErrors("User not found") }UserErrorsyou will know at compile time that you handle all cases. In fact in our backend code we havetype Result[T] = Either[GeneralError, T]to represent this andGeneralErroris defined asabstract class GeneralError extends Exception

So the point here is, I understand the argument that Try had issues, i.e. its hard to use Throwable in a general manner (because issue here is that Throwable is not an interface but rather a class so it has issues with mixin composition) but the solution wasn’t to suddenly turn Either into an some weird error type. One of the points of using such abstractions is that we want to use the most restrictive abstraction for the job, and that is not Either.

So to summarize in tl;dr format

- Almost never in code do I represent errors as

String's. It is too general and doesn’t compose. You always end up making either acase classor acase objectwhich encapsulates all of the details of the error so you can then match properly on the error - Try was supposed to be the original error type but probably set things up incorrectly by fixing the type to

Throwablerather than some other type ofTrait -

Tryshould support the right biasedmap/flatMap(since its not meant ot represent true unions) with methods likerecoverin case you want to move the left side into the result. The point of this is code clarity and conveying intent properly - You can also make an

Appilcativeerror types for accumulating errors which uses the same fixed type thatTry(orResultor w/e type we happen to use) - You should always use the most restrictive abstraction, this is not

Eitherfor handling errors.Eitherwas always used to represent tagged unions in a general way, even the docs reflected this, i.e./** Represents a value of one of two possible types (a disjoint union.) * An instance of `Either` is an instance of either [[scala.util.Left]] or [[scala.util.Right]].

Also I understand that with regards to composition of errors that Dotty should help here with union types however its not a full solution to the problems presented because

- You can’t use union types to compose

Either[String, Unit]to another errorEither[String, Unit]so you end up having to type your errors anyways - Dotty can represent the previous example using

UserNotFoundError | TweetNotFoundErrorhowever in our typical applications we have not 2 of these errors, but something greater than a hundred errors. Having to manually type these would be a massive PITA.

I also agree with the typed errors approach. IMHO it’s not the Either in Either[X, Y] or Result in Result[A, B] which make it a result-like thing. It’s the X or A. For example, if we have

Either[CustomerOrder, SuplierOrder]

it’s clear this is one of 2 kinds of orders. On the other hand, if we have

Either[ProcessingError, SuplierOrder]

(especially, if we have ProcessingError <: Exception), then it’s also clear this is some kind of a result of a fallible process. That makes me thing there is no problem with Either and that it works just fine for working with errors/results.

(There’s cats.data.ValidatedNec if we want to accumulate errors instead of failing fast.)