I take the view that in all 3 cases the arguments to the function should be marked as covered, but the shortcircuited statement should be marked as not covered.

in my view the method declaration should be marked as covered if the method is executed at all. I don’t think the coverage tool should try and calculate whether or not a particular lazy parameter has been accessed.

however instrumentation at the call site should indicate whether or not the supplied byName parameter was executed or not.

one possible naive solution to alot of these issues would be to introduce an invokeAround method to the Invoker class and wrap any statements in one of those calls (with some filtering).

method calls are problematic, but one solution to that could be nArity variations of invokeAround

for example

val a = ""

lazy val b = 1

def c = false

foo(x => x + x, a, b, c)

could be transformed to

val a = invokeAround("", ...)

lazy val b = {

invoked(...)

invokeAround(1, ...)

}

def c = {

invoked(...)

invokeAround(false)

}

invokeAround4(

(_1,_2,_3,_4) => foo(_1,_2,_3,_4),

invokeAround(x => x + x),

invokeAround(a),

invokeAround(b),

invokeAround(c), ...)

with the possiblity to drop some invoke arounds when a val is passed to a strict method parameter etc

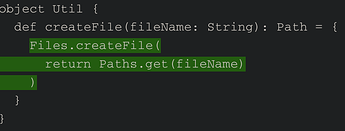

sudo implementation of invokeAround

def invokeAround[A](a :=> A, id: number, file: String): A = {

invoked(number, file)

a

}

def invokedAround1[A, Res](f: A => Res, param1: A, id: number, file: String): Res = {

// enforces strict evaluation of the parameters

// if a throw happens during evaluation of param1 then this code won't be reached

invoked(id, file)

f(param1)

}